Operation Highjump

This invasion of the continent of Antarctica was named Operation Highjump and comprised of some 4700 military personnel, six helicopters, six Martin PBM flying boats, two seaplane tenders, fifteen other aircraft, thirteen US Navy support ships and one aircraft carrier; the USS Philippine Sea (above). It seems incredible that so shortly after a war that had decimated most of Europe and crippled global economies, an expedition to Antarctica was undertaken with so much haste (it took advantage of the first available Antarctic summer after the war), at such cost, and with so much military hardware - unless the operation was absolutely essential to the security of the United States.

This invasion of the continent of Antarctica was named Operation Highjump and comprised of some 4700 military personnel, six helicopters, six Martin PBM flying boats, two seaplane tenders, fifteen other aircraft, thirteen US Navy support ships and one aircraft carrier; the USS Philippine Sea (above). It seems incredible that so shortly after a war that had decimated most of Europe and crippled global economies, an expedition to Antarctica was undertaken with so much haste (it took advantage of the first available Antarctic summer after the war), at such cost, and with so much military hardware - unless the operation was absolutely essential to the security of the United States.

At the time of the operation, the US Navy itself was being taken apart piece by piece as the battle-tested fleet was decommissioned with its mostly civilian crew bidding farewell to the seas forever. The Navy was even reduced to further recruitment to man the few remaining ships in service (1). Tensions across the globe were also mounting as Russia and America edged into a Cold War, possibly a Third World War that the US would have to fight with "tragically few ships and tragically half trained men (2)." This made the sending of nearly 5,000 residual Navy personnel to a remote part of the planet where so much danger lurked in the form of icebergs, blizzards and sub-zero temperatures even more of a puzzle.

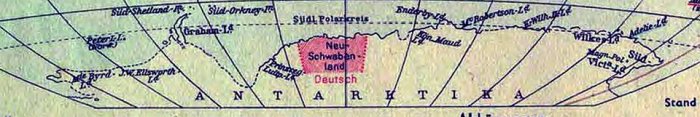

The operation was also launched with incredible speed, "a matter of weeks (3)." Perhaps it would not be uncharitable to conclude that the Americans had some unfinished business connected with the war in the polar region. Indeed this was later confirmed by other events and the operation's leader, Admiral Richard Byrd (above), himself. However, the official instructions issued by the then Chief of Naval Operations, Chester W. Nimitz, himself of German descent, were: to (a) train personnel and test material in the frigid zones; (b) consolidate and extend American sovereignty over the largest practical area of the Antarctic continent; (c) to determine the feasibility of establishing and maintaining bases in the Antarctic and to investigate possible base sites; (d) to develop techniques for establishing and maintaining air bases on the ice, (with particular attention to the later applicability of such techniques to Greenland) and (e) amplify existing knowledge of hydrographic, geographic, geological, meteorological and electromagnetic conditions in the area (4).

The operation was also launched with incredible speed, "a matter of weeks (3)." Perhaps it would not be uncharitable to conclude that the Americans had some unfinished business connected with the war in the polar region. Indeed this was later confirmed by other events and the operation's leader, Admiral Richard Byrd (above), himself. However, the official instructions issued by the then Chief of Naval Operations, Chester W. Nimitz, himself of German descent, were: to (a) train personnel and test material in the frigid zones; (b) consolidate and extend American sovereignty over the largest practical area of the Antarctic continent; (c) to determine the feasibility of establishing and maintaining bases in the Antarctic and to investigate possible base sites; (d) to develop techniques for establishing and maintaining air bases on the ice, (with particular attention to the later applicability of such techniques to Greenland) and (e) amplify existing knowledge of hydrographic, geographic, geological, meteorological and electromagnetic conditions in the area (4).

Little other information was released to the media about the mission, although most journalists were suspicious of its true purpose given the huge amount of military hardware involved. The US Navy also strongly emphasised that Operation Highjump was going to be a navy show; Admiral Ramsey's preliminary orders of 26th August 1946 stated that "the Chief of Naval Operations only will deal with other governmental agencies" and that "no diplomatic negotiations are required. No foreign observers will be accepted." Not exactly an invitation to scrutiny, even from other arms of the government. Admiral Byrd was a strategic choice as he was a national hero to the Americans; he had pioneered the technology that would be a foundation for modern polar exploration and investigation, had been repeatedly decorated, had undertaken many expeditions to Antarctica and was also the first man to fly over both poles. However, the task force itself, remained strictly under the military command of Rear Admiral Richard Cruzen.

The ships of the central group entered the ice pack off the Ross Sea on 31st December 1946 and found conditions as bad as had been noted for over a century. Icebreakers such as the USCGC Burton Island (below), a ship that had only recently been commissioned and was still undergoing sea trials off the Californian coast when Operation High Jump was launched, fought to cut a way through the ice to help the men land. (Again, pulling a newly commissioned ship off trials adds to the sense of the urgency of the overall operation.) The main force was divided into three groups. The Central Group comprised of the USS Mt. Olympus (communications); USS Yancey (supply); USS Merrick (Supply); USS Sennet (submarine); USCGC Burton Island (Icebreaker) and USCGC Northwind (icebreaker.) The East Group consisted of the USS Pine Island (seaplane tender); USS Brownson (destroyer) and the USS Canisteo (tanker).

The ships of the central group entered the ice pack off the Ross Sea on 31st December 1946 and found conditions as bad as had been noted for over a century. Icebreakers such as the USCGC Burton Island (below), a ship that had only recently been commissioned and was still undergoing sea trials off the Californian coast when Operation High Jump was launched, fought to cut a way through the ice to help the men land. (Again, pulling a newly commissioned ship off trials adds to the sense of the urgency of the overall operation.) The main force was divided into three groups. The Central Group comprised of the USS Mt. Olympus (communications); USS Yancey (supply); USS Merrick (Supply); USS Sennet (submarine); USCGC Burton Island (Icebreaker) and USCGC Northwind (icebreaker.) The East Group consisted of the USS Pine Island (seaplane tender); USS Brownson (destroyer) and the USS Canisteo (tanker).

"From the vibration of the great carrier", Byrd later wrote, "I knew when the captain had got the ship up to about 30 knots (35 mph). We seemed to creep along the deck at first and it looked as if we would never make it. But when our four JATO bottles went off along the sides of the plane with a terrific, deafening noise I could see the deck fall away. I knew we had made it (5)."

"From the vibration of the great carrier", Byrd later wrote, "I knew when the captain had got the ship up to about 30 knots (35 mph). We seemed to creep along the deck at first and it looked as if we would never make it. But when our four JATO bottles went off along the sides of the plane with a terrific, deafening noise I could see the deck fall away. I knew we had made it (5)."

Over the next four weeks the planes spent 220 hours in the air, flying a total of 22,700 miles and taking some 70,000 aerial photographs (6).